COVID-19 hits Uganda: livelihood impacts and mitigation measures scrutinized

by Teddy T. Nakanwagi and Dorothy Birungi Namuyiga*)

The global COVID-19 pandemic has exposed a lack of capacities and resources on the part of many central governments, especially in developing countries. Most governments seem to fail to cushion their people from the effects of a crushing economy and to put mitigation measures in place. Governments of developing countries are often frantic and seem to have no plans for disaster preparedness, especially with regard to essential services like health care, or the provision of food and water. In many countries, citizens find themselves having to deal with the pressure inflicted upon them as governments impose one COVID-19 mitigation package after the other.

Uganda’s approach of coping with COVID-19

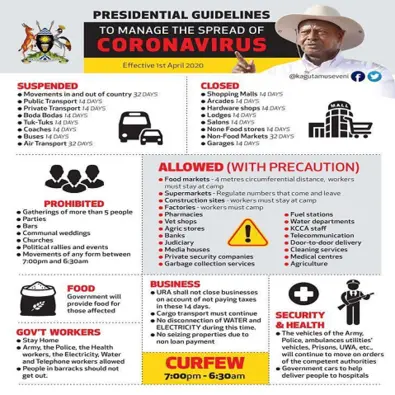

To minimize the devastating effects of COVID-19 on human health that were witnessed elsewhere, the government of Uganda moved to suspend some of the non-essential services even before the first COVID-19-case was confirmed on March 21, 2020. In a presidential address on March 18, 2020 President Yoweri Museveni announced that all education institutions were to close by March 20, 2020. The number and gravity of measures kept rising with each presidential address. On March 30, 2020 the President announced a partial lockdown and measures to be taken with immediate effect included a ban on public gatherings like church services and political rallies. As of April 1, 2020, the country was put under a full lockdown (see Ministry of Health website1) even barring the use of public transport and private vehicles. An exception was made for emergency cases such as pregnant women going for routine check-ups or deliveries and for essential workers. The public shutdown has affected access to essential services including food markets, health facilities, and the transport system. Its impact has been critical for the entire economy and life-threatening for the vulnerable poor who live from hand-to-mouth. As of April 30, 2020, the country had 81 confirmed cases, 54 recoveries, zero deaths and 27 active cases of which 18 are truck- drivers coming from neighboring Kenya and Tanzania.

Government’s response and parliament interference

The government has put different strategies in place to ease the effects of the lockdown for different sectors (figure 1b). As far as food security is concerned, the government promised and has started distributing food relief to the urban poor whose daily food consumption depends on a daily earning. A food relief package is a one-time composite of 6kgs of posho, 6kg of beans and 0.5kg of salt. Though rural areas suffer most from food insecurity (Diiro, 2017; GoU, 2017), priority was given to food-insecure people in the capital city of Kampala and the surrounding districts such as Wakiso.

This policy was based on the implicit assumption that people in rural areas can source food from their farms. Nevertheless, only about 42 percent of the households in rural areas derive food from their own production (UBOS, 2018). This entails that the majority of people living in rural areas depends on food purchasing and, in absence of income, their food security is just as much affected as that of people living in urban settings.

The plan of prioritizing food aid to the citizens of Kampala was contested by Ugandan Members of Parliament who even called for a delay in food distribution. Their argument was that it was not clear even to average Ugandans how the government arrived at this decision, taking into account that even prior to the COVID-19 pandemic rural areas had suffered from higher food insecurity than the urban centers did. The National Food Security Assessment report shows that before the pandemic outbreak about 26 percent of Ugandans were facing food insecurity (GoU, 2017) especially the urban and rural poor. However, the government’s COVID-19 task force under the office of the Prime Minister started distributing food relief to some areas around Kampala on April 4, 2020. Considering that Ugandan households have on average about five members (UBOS, 2018), the food aid package will last for approximately six days. This means that those who received food aid may have little advantages over those who did not, as it can sustain their families barely a week.

Call for donations

It was apparent from the start that the government’s centralized food distribution plan was insufficient to cater for the food needs of the majority of the vulnerable. Nevertheless, the president continued to bar private food distribution by any well-wisher citing it as a possible means of spreading COVID-19. The offender even faced being charged with attempted murder. The president encouraged anyone who has something to spare to donate it to the national COVID-19 task force. In response to that call various individuals and companies made generous donations, both in-kind and cash. By April 19, 2020, the COVID-19 task force had collected in-country donations amounting to 4.5 billion UGX (about $ 1.2 million2).

The difficult role of local leaders

The banning of unofficial food donations has put local leaders in a difficult situation. Though the role of local leaders (for example village chairpersons) in providing welfare to their constituencies was not endorsed by the COVID-19 task force and the president, citizens have continued flocking to their leaders’ residences to ask for food during the lockdown period. The local leaders or neighbors who have dared to give out food have been arrested for the crime of attempted murder. One of them was Member of Parliament Mityana, Hon. Francis Zzaake, who was arrested on April 20 for having distributed food to members of his constituency. The arresting of local leaders and well-wishers who are trying to help the needy may not only be affecting current generosity but even future generosity of Ugandans. Yet, in an economy with a potential upcoming recession (World Bank, 2020) and a government which can barely meet the need for food of a quarter of its population, good-will Ugandans will have to play a role in securing food for both urban and rural poor who survive from hand-to-mouth.

Our policy recommendations

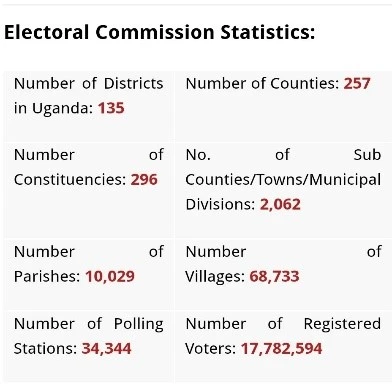

With several gaps in the governmental food distribution structure, we propose a more decentralized approach targeting the village-level. Uganda currently has 68,733 villages (figure 2). For future reference and proper food distribution, any pandemic task force should obtain rough estimates of the number of households that have been, are currently and will likely be food insecure. The national task force should be working in strong liaison with village local councils. We further suggest creating an account number (mobile money or bank account) for each village, with local village councils, especially the welfare committees, and chairpersons being the signatories. To enable donors to contribute to villages of their choice, village names and their accounts could be displayed on the local government website. The government can promote its efforts through mobilizing the public to donate to their fellows in need, as well as sensitizing the public on thrift expenditures and maximize savings.

Furthermore, we propose that the Ugandan government identifies more suitable and cheaper suppliers of essential food items like maize, beans, soya and millet floor, silver fish within the country. While the village welfare committee could oversee the contracting of the suppliers, place orders of needed supplies and sign the cheques for the supplier, the Uganda National Bureau of Standards should be in charge of monitoring the quality of food before it is supplied to beneficiaries.

There must be a mechanism enabling local village leaders to file a complaint if the services of the supplier are unsatisfactory. To increase accountability and transparency to the donating public, everyone should be able to see the status of the village accounts and if money was withdrawn the names and contacts of those who benefited should be displayed on the website too. Considering that internet infrastructure and digital know-how in rural Uganda are very limited, the targeted internet application should be easily accessible.

-------

1) https://www.health.go.ug/covid/

2) Exchange rate as of 26/04/2020: 1USD= 3750UGX

Authors:

*) Teddy T. Nakanwagi is a PhD candidate at CAES, Makerere University, Kampala, Uganda

Dorothy Birungi Namuyiga is a junior researcher at the Right Livelihood College (RLC) Campus Bonn, Center for Development Research (ZEF), University of Bonn, Germany and a scientist at the National Agricultural Research Organization (NARO), Uganda

References:

Diiro, G.M. (2017). Ending Rural Hunger: Case of Uganda

Government of Uganda (GoU). (2017). National Food Security Assessment. January 2017

Uganda Bureau of Statistics (UBOS), 2018. Uganda National Household Survey 2016/2017. Kampala, Uganda; UBOS.

World Bank (2020). For Sub-Saharan Africa, Coronavirus Crisis Calls for Policies for Greater Resilience. https://www.worldbank.org/en/region/afr/publication/for-sub-saharan-africa-coronavirus-crisis-calls-for-policies-for-greater-resilience?cid=ECR_TT_worldbank_EN_EXT accessed 16/4/2020