Poverty, growth and productivity gaps in Bangladesh and Orissa, India

Trip report by Franz Gatzweiler, Center for Development Research (ZEF), University of Bonn, Germany

From Oct 26 to Nov 12, 2011 I visited Bangladesh and India. I had the chance to see rice growing areas in the Central-West of Bangladesh as well as rainfed upland and flood prone rice agro-ecosystems in the Indian state of Orissa. In Bangladesh I visited the irrigated and flood prone areas of Bogra, Naogaon and Rajshahi and back to Joydepur/Gazipur. In Orissa we visited some villages around Nayagarh (about 85 km West of Bhubaneswar) and the flood prone rice growing areas all the way from Cuttack to Paradip port. Nayagarh is one of the districts in Orissa were rice cropped area is the largest (>60%), yield gaps are the highest (> 200%) and rice yields are the lowest (< 1.5 kg/ha).

The purpose of my visit was to prepare for a project which, among others, aims at assessing rice cropping technology innovations in Orissa and Bihar as well as in Bangladesh and which have the potential to increase productivity and benefit the rural poor. Key questions are: what are the main barriers for productivity growth in rice growing areas in which agricultural and human potentials are high but not or insufficiently made use of and where rural poverty prevails?

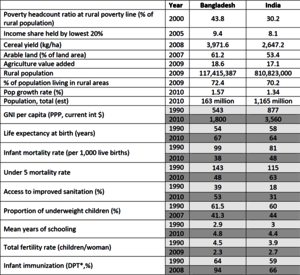

Both India and Bangladesh have progressed towards many development indicators. From 1990 to 2010 India’s GNI per capita has increased fourfold while that of Bangladesh has increased threefold. Life expectancy at birth has improved and the infant mortality rate has halved in India and decreased nearly threefold in Bangladesh. With 19% value added from agriculture to GDP in Bangladesh, the agricultural sector is more important than in India where it contributes with 17%. Table 1 shows other indicators and compares both countries.

Although Bangladesh is doing less well than India in terms of per capita growth it has overtaken India in terms of basic social indicators, such as life expectancy, infant survival, fertility rates, immunization rates, mean years of schooling, access to improved sanitation, and proportion of underweight children. These positive developments also show when looking at the Global Hunger Index (GHI). From 1990 to 2011 Bangladesh has improved its GHI twice as much than India (although Bangladesh still ranks 70 and India 67).

If we take a closer look at the GHI composite indicators, they show that the proportion of underweight people as part of the entire population has remained more or less the same in India (20%) while it has reduced by 11% (from 38 to 27%) in Bangladesh. Improvements (from 1990 to 2009) in the other composite indicators are also better in Bangladesh than in India: Reduction of the proportion of underweight children under 5: 20.2% in Bangladesh; 16% in India. Mortality rate for children under 5: 9.6% in Bangladesh; 5.2 in India.

These numbers signal rather clearly that there is not necessarily a link between economic growth measured in per capita income and poverty reduction – unless policies are in place which give attention to rural development, institutional reform and structural transformation. Obviously, if returns from economic growth are not invested in the improvement of public services, social security schemes, agricultural development, infrastructure development, research and education and other sectors which contribute to structural change, it will be difficult to reduce poverty, reduce income inequality and achieve inclusive growth.

The income inequality in India reflects this development symptom as well: While the top 10% of India’s population enjoys 31.1% of the country’s income, the lowest 10% suffers with merely 3.6%. While India has an income gini coefficient of 38.6, Bangladesh has one of 31 (as a comparison, Norway: 25.8 and Guatemala: 53.7). Not surprisingly IFAD puts India into the group of countries which have a “high level of hunger and slow progress in improving it” whereas Bangladesh is in the category of “high level of hunger and rapid progress in improving it”.

The income inequality in India reflects this development symptom as well: While the top 10% of India’s population enjoys 31.1% of the country’s income, the lowest 10% suffers with merely 3.6%. While India has an income gini coefficient of 38.6, Bangladesh has one of 31 (as a comparison, Norway: 25.8 and Guatemala: 53.7). Not surprisingly IFAD puts India into the group of countries which have a “high level of hunger and slow progress in improving it” whereas Bangladesh is in the category of “high level of hunger and rapid progress in improving it”.

One can get the impression that policies are prioritized in India which are based on the belief that India wants to buy itself onto the development path and out of poverty, e.g. by food subsidies (such as the "rice-at-Rs2 per kg" scheme) or fertilizer subsidies. But it is becoming more apparent that this is not what “inclusive growth” is about. Cash transfers (conditional or unconditional) are a good complimentary measure but cannot replace functioning public services. And if there is no functioning extension service in agriculture and investments in rural infrastructure, insular policies like fertilizer subsidies will not fall on fertile grounds.

If productivity growth is the pathway out of poverty for smallholders in South Asia, then Bangladesh is currently on a better way than India. Whereas Bangladesh has managed to increase cereal yields per ha from the 1970s onwards and from 1990 to 2009 by 50%, India managed to increase yields per ha only by 28% within the same time period.

* diphtheria, pertussis and tetanus.

Table Sources: Jean Drèze and Amartya Sen. 2011. Outlook India. The weekly news magazine. Cover story. Nov.14, Vol LI, No. 45, pp.50; Human Development Report 2011; ruralpovertyportal.org; World Bank data